Throughout church history, there have been a number of noteworthy heresies, such as Arianism (the denial of Christ’s divinity) or Nestorianism (Christ’s divinity and humanity are entirely separated). The heresy of Donatism is another heresy that arose in the early church and at a time when Christians were being persecuted for their faith by the Roman Empire.

What is Donatism, why is it a controversial heresy, and what were its lasting effects? We'll explore the answers to all these questions below.

What Is Donatism?

The period is the early second century: Co-emperors Galerius and Diocletian rule. Christians are heavily persecuted. Christians, by the hundreds, are tried, tortured, and executed for their faith. The persecution is widespread and affects Christians from all walks of life.

This persecution involved not only physical and bodily torture but also tested the minds and spirits of believers to see if they would stand strong in their professed faith in Christ. Like the apostles, many Christians endured until the end, ultimately becoming martyrs for their faith at the hands of the Roman Empire.

Others broke under torture and fell into apostasy. These former Christ-followers recanted their faith in the face of torture. Like the Apostle Peter who denied Christ before His crucifixion, many of these Christians felt great shame after recanting their faith. Many sought repentance and penitence for denying Christ under the fear of torture.

After Constantine the Great legitimized Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) and adopted the faith in the new capital, Constantinople, persecutions ceased. As anyone can imagine, this allowed Christians to come out of hiding and openly profess their faith. With this came believers who had confessed and repented for turning from the faith during persecution.

While many accepted the faith of these Christians who had denied Christ when faced with persecution, one group did not. This group became known as the Donatists and their views became known as Donatism.

Who Is Donatism Named For?

Donatism was named after its proponent, Donatus, a 4th-century Christian bishop in North Africa. The Donatist movement arose in response to the persecution of Christians and, specifically, the debate over the validity of sacraments performed by clergy who had lapsed in their faith under persecution. DDonatists believed that the validity of sacraments, such as baptism and the Lord’s Supper, depended on the moral purity and faithfulness of the clergy administering them. They rejected the idea that sacraments performed by priests who had lapsed during persecution could be valid. Donatists emphasized a pure and holy church, arguing that clergy who had betrayed the faith could no longer lead or perform sacraments. This strict stance led to a major schism in the early church, particularly in North Africa. The Donatist controversy highlighted early church struggles over holiness, forgiveness, and the role of clergy.

What Made Donatism Controversial?

Christians residing in North Africa did not take too kindly to apostates returning to the faith, especially clergy. When clergy returned to the fold and were reinstated, these Christians viewed the clergy’s administering of the sacraments as invalid.

One Christian greatly affected was Bishop Caecilian of Carthage in 311 AD. This was due to his being consecrated as a bishop by Bishop Felix, who surrendered Scripture manuscripts under Emperor Diocletian’s persecution. As a result, Bishop Caecilian was called to be removed. Caecilian was replaced by Majorinus, who was in turn replaced by Donatus. Doatus preached and taught that all Christians who had surrendered manuscripts of the faith or who had betrayed other Christians, or recanted their faith under persecution could not be reinstated to their former positions. Donatus and his followers held that these apostates should be denied Holy Eucharist.

This controversy developed into a major schism in the church, and Emperor Constantine the Great even became involved. Emperor Constantine and the Council originally found Caecilian innocent of his charges. However, this did not sway Donatus or his Donatist followers in their views.

How Long did Donatism Last?

While Emperor Constantine oversaw the council’s decision on the matter, he was not the deciding factor. When a hearing was instituted to view Donatus’ case to remain bishop, Constantine left it to the church to decide. Originally, Constantine appointed three Bishops to hear the case. After his leave, however, 15 more Bishops were added to the hearing without the Emperor being notified. Denied by the Church, Donatus was ousted and removed from his role as Bishop. As a result, he pleaded a second time with the Emperor. A second hearing was given. Ultimately, the second hearing’s results were the same. At this point, Donatus and the Donatist were becoming branded as heretics.

The church’s reason for labeling Donatists as heretics can be boiled down to the sacrament of penance (or confession) and Christ atoning for the sins of the world (Galatians 1:4). In Roman Catholicism, Eastern and Coptic Orthodoxy, Anglican Catholicism, and high church Protestantism, confession is where the penitent person confesses their sins to God with a priest as a witness and spiritual father who can offer direction and counsel. After this, the penitent is absolved of their sins in the Holy Trinity and is given penance. The sacrament is rooted in Christ’s atonement and the call to confess sins to one another (James 5:6). If Christ atoned for our sins, and we confess our sins to God (who is loving and merciful), what makes apostasy an unforgivable sin where communion is withheld and ordination rites stripped without a second chance?

Despite the result of the second hearing, Donatus pleaded with the Emperor a third time. Constantine begrudgingly gave a third hearing. The division grew beyond theological disagreement, resulting in violence between the Donatists and the church. While wanting to unite the church, Constantine had a civil war back in Constantinople and left it to the church to handle.

As a result, the Donatists were tolerated until 347 AD. Under Emperor Constans I, the Donatists were exiled to Gaul (modern-day France). This was not to last. Under Emperor Julian (also called Julian the Apostate), the Donatists managed to return to North Africa in 361 AD. The church, including notable figures like St. Augustine of Hippo, still managed to put the Donatists in their place. Through another council in 411 AD, Donatists were separated from the church and denied ecclesiastical rights by law. Despite this, the Donatists survived under foreign rulers such as the Visigoths and then again under Byzantium well into the seventh century.

While Donatism does not widely exist today, some Christian denominations, namely Baptists, claim to have roots in the early church through the trail of blood theory and name Donatists as part of the lineage. It should be noted that Baptists do not widely hold Donatism, but the history is worth noting nonetheless.

Can We Learn Anything from Donatism Today?

Donatism reveals a powerful lesson for Christians today. It shows how legalistic Christians can become when we negatively look down upon returning apostate Christians while praising St. Peter, who also denyed Christ three times (Matthew 26:69-75) and was later forgiven, and went on to become a bold voice of the early Christian Church. If we are not careful, we can gatekeep people from the faith similarly to the Donatists. This is not to say that the church should not take returning apostates seriously, but totally denying them is un-Christlike. Furthermore, it goes against the foundations of faith regarding confession, forgiveness, compassion, and atonement.

For Further Reading

Donatists Dug in Heels in North Africa

A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists

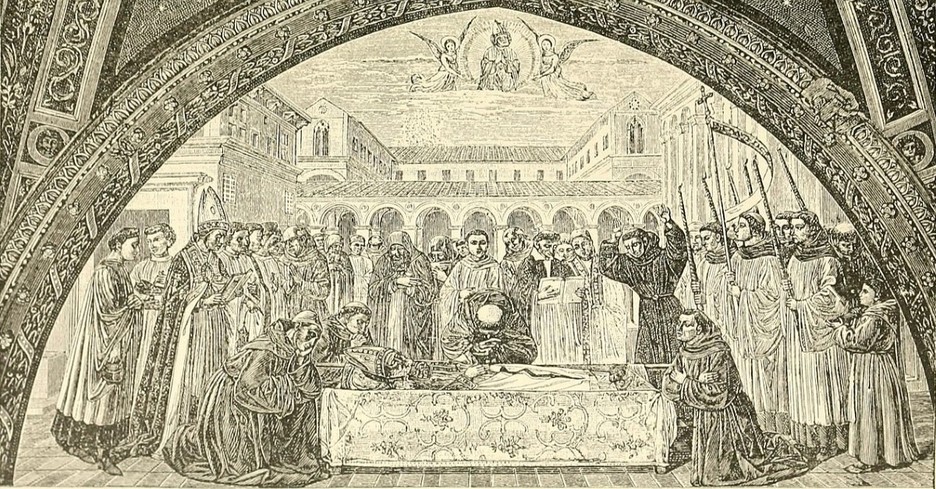

Photo Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons