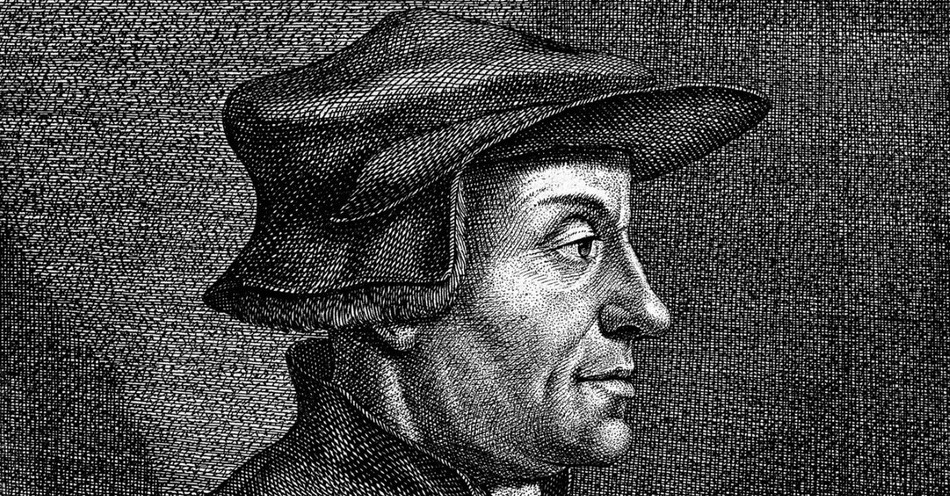

Ken Curtis and Dan Graves examine the dramatic story of Swiss Reformer Ulrich Zwingli.

Reform Under Zwingli

Born in Wildhaus, Switzerland, on New Year's Day in 1484, Zwingli received a good education in the classics and was ordained a priest in 1506. He served as parish priest in Glarus from 1506 to 1516.

Opposing "blood for gold"

A key event during that period aroused his patriotic fervor and perhaps began to undermine his confidence in the Roman church. One of the major industries for the Swiss then was mercenary service. They would hire out their young men to fight in others' wars, including battles for the pope. (You can still see the Swiss guard today policing the Vatican in their colorful uniforms). Zwingli accompanied the Swiss troops as chaplain in September of 1515, and saw 6000 of his young countrymen slaughtered in the service of the pope at the battle of Marignan in Italy. He returned home determined to abolish this mercenary practice of "selling blood for gold." It would cost him his parish at Glarus but helped pave the way for his call to Zurich later.

The year 1516, was decisive for him. He moved on to become priest at Einsiedeln, apparently put a sexual affair with a barber's daughter behind him, and met the great scholar Erasmus. He immersed himself in the Greek New Testament published by Erasmus. (He actually hand copied out of this edition all of Paul's epistles and learned them by heart.) His preaching began to take on a decidedly evangelical tone.

On January 1, 1519, his 35th birthday, he became pastor at the central church in Zurich. Here he was able to work toward the prohibition of mercenary service. As soon as he arrived, he announced that, rather than preach from the prescribed texts of the lectionary, he was going to preach through the Gospel of Matthew. This was a bold step in that day.

The dreaded plague arrived in Zurich the same year as Zwingli. He did his best to minister to his people. More than one-fourth of the 9,000 people of the city fell victim. Zwingli caught the plague, too. In his three-month recovery, he learned life-changing lessons of dependence on God that made his trust in God's Word rock-solid.

A city council debates theology

The rituals and doctrines of the Church did not square with his reading of Scripture. He preached what he found in the Bible--even when it meant going against long-accepted church teachings. As a result, controversy spread. A public debate was held on disputed matters of faith and doctrine by the Zurich city council. On January 29, 1523, the council issued a ruling backing Zwingli and issued a decree that he and the other pastors in the region were "to preach nothing but what can be proved by the holy gospel and the pure holy scriptures."

Reforms were implemented, Catholic images removed, the mass replaced with a simple service emphasizing preaching, and communion celebrated more as a "spiritual" reception of Christ.

Resistance from within and without

Despite this vote of confidence, Zwingli could expect that the Catholic loyalists would resist him, and they did. He did not expect that perhaps his greatest trials would come from within--some of his closest followers did not think he was pressing the reforms fast enough. These became known as Anabaptists. They were particularly agitated over infant baptism, which they rejected. Another public debate was called to consider the issue. The Zurich council ruled against the Anabaptists, so these "radicals" defied the council. They "re-baptized" themselves as adult believers. When they continued to defy the council, some of the radicals were put to death.

Hacked to pieces

This tragedy from within was compounded as civil strife intensified between Catholic and Protestant areas. Zwingli's reform movement did take hold in major urban centers of German-speaking Switzerland and eventually would find reception in Geneva, paving the way for Calvin's work there. But Catholic resistance, particularly in rural cantons, could not be overcome. Fighting broke out. Zwingli joined the Zurich troops as an armed soldier against the Catholics in what is known as the second Kappell War. The same Zwingli who had worked so hard to eliminate the mercenary service and had earlier even condemned war itself now took up arms, convinced it was necessary in the service of God and the Gospel. He was killed in battle on October 11, 1531, his body hacked to pieces and disgraced by his enemies.

Wars of religion would continue in Europe for well over a century after the Reformation. All of the major power centers calling themselves Christians--Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed alike--would look to the power of the state and the sword to preserve and advance their interests.

Giants unable to agree

Luther and Zwingli meet at the Colloquy of Marburg, October 1529 The reforms under Luther in Germany and Zwingli in Switzerland had many parallels, and the two agreed on most essential points of doctrine. Philip Landgrave of Hesse was eager to join their movements in political, military, and religious unity, thereby strengthening the Protestant front against the growing Catholic pressure. He brought the two of them together to meet in doctrinal discussion at Marburg. Fifteen articles of faith were on the agenda and agreement was quickly reached on fourteen of them. But on the remaining item--the Eucharist--no concord could be reached and the trading of insults turned ugly.

Zwingli interpreted the presence of Christ in the Eucharist in a more spiritual and metaphorical way than Luther could accept. Thus a significant opportunity for expanded unity within the Protestant movement ended in division. Argument over the Lord's Supper--a sign of the oneness of God's people, rather than bringing together these two stalwart defenders of Scripture, instead drove a mean wedge between them.

("Reform Under Zwingli" by Ken Curtis, PhD, published April 28, 2010 on Christianity.com)

Zwingli Perished by the Sword

Ulrich Zwingli was born the first of January 1481. The world he entered was passing into a spiritual and political ferment in which he would be a prime mover. As a boy he distinguished himself at studies and music. He determined to become a priest and was ordained at the age of 23.

Zwingli hand-copied and memorized Paul's letters in the original Greek. Impressed by the reform writings of the great humanist scholar Erasmus, he moved toward reformation even before Luther. The use of young Swiss men as mercenaries especially evoked his ire. Having accompanied two expeditions as a chaplain, he spoke vehemently against the practice which squandered their blood. As priest of Einsiedeln, a city whose income came from pilgrimages, he preached against pilgrimages, too, labeling them a corruption. When an indulgence was sold in Switzerland, he denounced it.

The first day of 1519 Zwingli came to Zurich, the city of his life's work. There he continued his battle against indulgences. The Pope recalled the seller. Zwingli also announced that he would not read the prescribed lessons but preach the gospel of Matthew instead. He did so, pouring forth objections to the use of images in the church, to the mass and other practices of the church which he considered to be in error. Christ alone is sufficient for salvation, he said.

It is one of the interesting characteristics of the Swiss Reformation that local leaders voted on doctrine, making religious decisions for their constituents. This practice of Zurich was followed by other Swiss Protestants and was one of the stages that led toward the creation of modern democracy.

Zurich's town leaders took to heart Zwingli's teaching. It was they, not Zwingli, who ordered that the Holy Scriptures be taught "without human additions." It was they who challenged theologians to convict Zwingli of error if they could. It was they who ordered images removed from churches.

Protestant and Catholic in Switzerland remained at odds. The Protestants established a blockade, threatening Catholics with starvation. In 1531 the Catholic cantons marched against Zurich. Zurich's forces ordered Zwingli to take the field bearing their banner.

1,500 men from Zurich faced 6,000 from the Catholic cantons. Under feeble generalship, on badly chosen ground near Kappel, they made critical errors. Failing to maul their opponents at an opportune moment, they allowed them to gain the cover of a beech wood. Then they did not retreat to a safer line while able. About 4:00 PM on this day, October 11, 1531 the Catholics began the assault. Half an hour later the Protestants were wiped out. Zwingli was among the dead. His body was quartered and mixed with dung. Told the news, Martin Luther, who disliked Zwingli, replied, "all who take the sword die by the sword."

Bibliography:

- Adapted from an earlier Christian History Institute story.

- Dowley, Tim. Eerdman's Handbook to the History of Christianity. Carmel, New York: Guideposts, 1977.

- "Zwingli, Ulrich." Encyclopedia Americana. Chicago: Americana, Corp. 1956.

- Potter, G. R. Zwingli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Simon, Edith and the editors of Time-Life Books. Great Ages of Man. The Reformation. Time-Life, 1966.

- "Zwingli, Ulrich." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

Last updated July, 2007

("Zwingli Perished Under the Sword" by Dan Graves, MSL published on Christianity.com)

Bullinger replaced Zwingli in Zurich

Ulrich Zwingli, reformer of Zurich, died in the battle of Cappel, carrying the banner for Zurich's forces. A man of great originality--his reforms began a year before Luther's--he seemed irreplaceable. But on this day, December 23, 1531, Heinrich Bullinger took over the vacant pulpit of Zurich. A contemporary of Calvin, he is remembered as a notable reformer in his own right, a kindly man who did not allow small doctrinal differences to separate him from other reformers.

Like others of that generation, Bullinger's training was in the Church of Rome. Born in Bremgarten, Switzerland, he studied in a local monastic school before moving on to the University of Cologne. Wishing to compare the teaching of the Roman Church with that of Luther, he read Luther and Melanchthon. His investigation broadened out to include thinkers of the early and medieval church. He came to the conclusion that doctrine must be derived from scripture. He became a Lutheran, but later preferred the doctrines of Zwingli.

In 1529, he married Anna Adlischweiler, a former nun. This step was not hard for him. His father, also a Church of Rome priest, had set the example by paying his bishop a yearly fee for permission to maintain a wife. Bullinger later convinced his father to leave the Roman Church and the elder Bullinger immediately married the woman with whom he had faithfully lived for so many years.

Bullinger's married life was happy. Warmhearted, he delighted in his children and grandchildren. Some men drive their children to rebellion. All of Bullinger's sons became Protestant ministers. His hospitality to refugees from Queen Mary's England (on a tiny salary), made him influential with the Church of England when it was reestablished. The Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England show his influence. His Decades, a book of sermons on key doctrines, was reprinted 79 times in England within a single century. The Puritans took him as their guide.

Bullinger was a key player in drafting the two Helvetic Confessions that unified Switzerland's faith. (Helvetia was the Latin name for Switzerland.) The second confession, in fact, was originally drawn up as his own personal statement of faith, but became the most broadly accepted reformed confession, agreed to by reformed movements in half a dozen nations.

A typical statement from the Second Helvetic Confession is direct and clear. "Christ Is True God. We further believe and teach that the Son of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, was predestinated or foreordained from eternity by the Father to be the Savior of the world. And we believe that he was born, not only when he assumed flesh of the Virgin Mary, and not only before the foundation of the world was laid, but by the Father before all eternity in an inexpressible manner. For Isaiah said: 'Who can tell his generation?' (Ch. 53:8). And Micah says: 'His origin is from of old, from ancient days' (Micah 4:2). And John said in the Gospel 'In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God,' etc. (Ch. 1:1). Therefore, with respect to his divinity the Son is coequal and consubstantial with the Father; true God (Phil 2:11), not only in name or by adoption or by any merit, but in substance and nature, as the apostle John has often said: 'This is the true God and eternal life' (1 John 5:20)..."

Some denominations, such as the Puritans of New England, emphasize covenant theology. Bullinger was the first reformer to write an important work on the subject. He argued that both Jews and Gentiles participate in the same Abrahamic covenant by faith.

As surprising as it may sound, Bullinger wrote more than Luther and Calvin combined.

Bibliography:

- "Bullinger, Heinrich." The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

- "Bullinger, Heinrich." New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1954.

- Zwingli and Bullinger; selected translations with introductions and notes by G. W. Bromiley. London: S C M Press, 1953.

- Various encyclopedia and internet articles.

Last updated May, 2007.

("Bullinger replaced Zwingli in Zurich" by Dan Graves, MSL published April 28, 2010 on Christianity.com)

Photo Credit: © Getty Images/Photos.com

This article is part of our People of Christianity catalog that features the stories, meaning, and significance of well-known people from the Bible and history. Here are some of the most popular articles for knowing important figures in Christianity:

How Did the Apostle Paul Die?

Who are the Nicolaitans in Revelation?

Who Was Deborah in the Bible?

Who Was Moses in the Bible?

King Solomon's Story in the Bible

Who Was Lot's Wife in the Bible?

Who Was Jezebel in the Bible?

Who Was the Prodigal Son?

.jpg)