We know that there are about 15 passages in the New Testament in which people refer to Jesus as a rabbi. We may have an image of what a rabbi is based on rabbis we meet today… but the Bible does not ever mention Jesus being part of the formal priestly groups in Jerusalem. So, was Jesus a rabbi in the conventional sense, or did something keep him from being a rabbi? If he was not a rabbi, what does that tell us about his ministry?

To answer these questions, we need to take a look at the context of rabbis in Jesus’ time, and how the concept of being a rabbi informed why people found him so shocking.

What Does the Word Rabbi Mean?

If someone is called a rabbi today, we think of a pastor or priest for Judaism: someone who works full-time as a religious teacher, either teaching in a school or leading a local congregation. That is more or less what the word meant in ancient times, although the term suggested a kind of reverence that we may miss today.

As Strong’s Concordance shows, the word “rabbi” shows up in the Greek versions of the four gospels, based on a Hebrew term meaning greatness. Avner Shamir explains in an article for the Journal of the Bible and Its Reception that calling someone a rabbi literally means to say, “My great one.” The gospels also feature the word “Rabboni,” the title Mary Magdalene calls Jesus when she meets him after his resurrection. This is a more personable version of “rabbi,” meaning “my greatest teacher.”

Scholars debate whether the term “rabbi” was used much during Jesus’ time, but agree that becoming a rabbi required a lot of training. A kind of training that looked very different than seminary does today.

How Would Jesus Have Trained to Be a Rabbi?

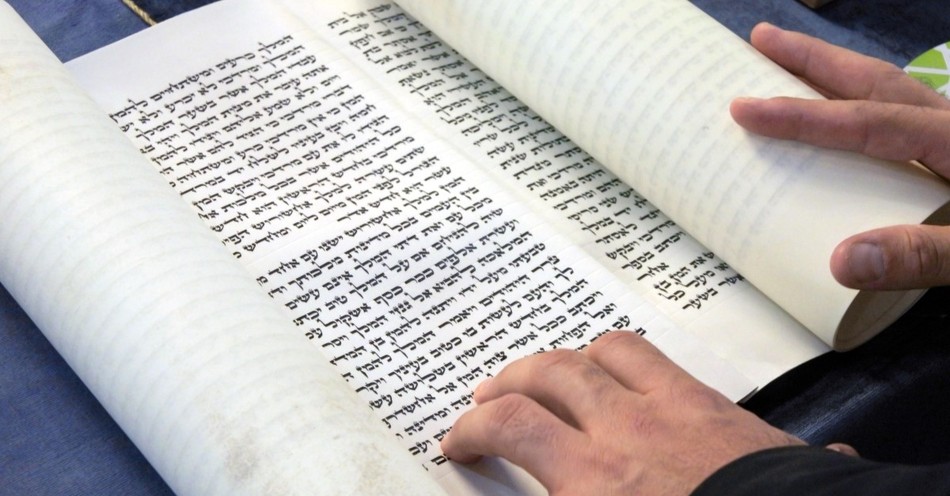

To become an ordained rabbi (or teacher of the law) in Judaism, Jewish boys had to study the Torah—the first five books from the Hebrew Bible, the core books that all followers of Judaism agreed were inspired:

- Genesis

- Exodus

- Leviticus

- Numbers

- Deuteronomy

In fact, some experts claim rabbinical candidates had to essentially memorize the Torah. Around 13, the year that Jewish boys were ceremonially declared to be young men instead of children, a rabbi seeking students would test the candidates. Boys who passed the test would then spend years being apprenticed by their teacher: studying all of their teachings, sharing a home with them, imitating how the teacher lived as well as what they said or taught. Students were known for walking behind their teachers so closely that the dust from the teacher’s footsteps caught on the student’s robes. Literally, a student walked “in the dust of the rabbi.”

Eventually, candidates would finish their training and become teachers of the law at their local synagogue. The synagogues were developed after the Babylonians invaded Judea and destroyed Solomon’s temple, offering a way for Jews to meet locally and learn Scripture. By Jesus’ period, Jews had returned to their homeland and had a new temple (the famous Second Temple, renovated by Herod the Great), but most Jews still used synagogues to learn about God. They only went to Jerusalem’s temple for major festivals like the Passover. So, local teachers of the law and scribes functioned much like local pastors or priests today.

How rabbis understood Scripture and directed people depended on which sect they followed. The teachers with strong connections to Jerusalem and other major cities often belonged to the Sadducees, who sought to please the Romans and interpreted the Torah in progressive ways. Others belonged to the Pharisees, who emphasized meticulously studying Scripture (the Torah and later books). Saul of Tarsus (later known as the apostle Paul) mentions that he was a Pharisee before he joined the early church. The Pharisees later became the basis for modern-day rabbinical Judaism.

Although many of his followers (and sometimes rivals) called Jesus “rabbi,” all the evidence available says he was not an ordained teacher of the law. Passages like Mark 6:3 indicate that Jesus worked as a carpenter (the word may mean he worked with both stone and wood) in a small town called Nazareth, just like his legal father Joseph had (Matthew 13:55).

But why was Jesus not a vocational rabbi then?

Why Was Jesus Not a Professional Rabbi?

Scholars have suggested several reasons why Jesus did not become an ordained rabbi. Bruce Chilton emphasizes in his book Rabbi Jesus that Mary’s pregnancy with Jesus before she married Joseph meant Jesus was a mamzer (a son of dubious heritage), making it difficult for him to become an ordained priest. This could be correct, but the answer is likely more mundane: most people in ancient societies worked in the same profession as their parents, because changing careers required resources (access to local teachers, money to pay teachers) that the average family did not have.

Many books and articles claim all Jewish boys in Jesus’ time received primary school education where they carefully studied the Torah until they were 13 years old, then decided whether to become rabbis or enter the family business. Catherine Hezser discusses in several works, including her chapter on education for The Oxford Handbooks of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine, that these claims are based on sources written centuries after Jesus’ time. The earliest documents suggest there were few public schools in Jesus’ time, which is not surprising. Widespread public schooling requires strong government structure and money to maintain it (which few small first-century nations had). Even if Judea had the resources, the Roman Empire probably did not want widespread public education in nations it ruled. Well-educated populations tend to ask inappropriate questions, like “Why are we being ruled by a foreign power?”

Therefore, only Jewish families with the right money, history, and connections sent their sons to be trained as rabbis. Everyone else focused on training sons in the family trade, like Zebedee training his sons James and John to catch fish (Matthew 4). Jesus’s earthly father was a carpenter, so Jesus became a carpenter; until he was about 30, when he went to meet John the Baptist, was baptized, and after testing in the desert, spent three years teaching and healing people around the country. While ordained rabbis lived on money from parishioners or other sources, Jesus lived during those three years on money from benefactors, including a woman named Joanna whose husband managed King Herod’s palace (Luke 8:3).

Which brings us to the most important question: why did people call Jesus a rabbi if he was not an ordained rabbi?

Why Did People Call Jesus a Rabbi?

We know that people call Jesus “rabbi” about 15 times, including verses like Matthew 26:25, John 1:38, and John 11:8 (in fact, he especially gets called “rabbi” in John). Other times, people call him “teacher.”

There are several possibilities for why this is.

First, many Jewish people may have called their mentor or leader a “rabbi” to convey respect. Self-taught religious teachers were fairly common in Jesus’ day, not just because schooling was rare, but because it was a volatile time. As Gamaliel comments when talking to the high priests in Acts 5:33-39, many men were trying to start political or religious revolutions. Many of these would-be saviors claimed to be the Messiah the Old Testament talked about, although only Jesus fulfilled all of the messianic prophecies. People who wanted Jesus to mentor them or believed he was the Messiah (his disciples, potential students like Nicodemus) called him “rabbi” to show they respected him. People who disliked him (the Pharisees) usually called him “teacher,” a polite term but with less reverence.

Second, scholars like Mark Verman argue that “rabbi” was a rare term in Jesus’ time, but the writers of the gospels use it to make a special point: Jesus was the Great Teacher, the long-awaited Messiah. This theory would explain why the Gospel of John uses “rabbi” the most. This gospel highlights the fact that Jesus was God, and was written decades after the other three (at a time when Jews were starting to use “rabbi” a lot more).

Does It Matter Whether Jesus Was a Rabbi?

It is interesting to wonder if Jesus being called rabbi was a clue to the original readers that he was something unusual, not just a teacher, but The Great Teacher, the long-expected Messiah. However, the more important thing is that Jesus being called a rabbi tells us crucial things about his ministry.

First, it gives a sense of how closely his disciples followed him. They traveled with Jesus for three years, trying to imitate the way that rabbinical students lived: living with their teacher, closely examining everything the teacher did, trying to become the closest copy they could be of the rabbi. Jesus carefully tells his disciples not to let their future followers call them “rabbi” (Matthew 2:38), because he is the rabbi for the whole church. We are all seeking to be discipled by Jesus, to know him intimately.

Second, it helps us understand tensions between Jesus and his audience. Rabbis were great learned men whom everyone respected. Jesus lacked a rabbi’s training, but his miracles and his message conveyed power that the best rabbis lacked. When Jesus preached in his hometown of Nazareth, people couldn't understand how the local carpenter had become a gifted teacher of Scripture (Luke 4). When Pharisees saw Jesus preaching, they were irritated that someone who never had time to memorize the Torah could interpret it better than they could.

Third, the emphasis on Jesus being “the great teacher” underscores that Jesus was something special. Whether the gospel writers were trying to hint at Jesus being the Son of God by using “rabbi,” there are many ways that all four gospels indicate that Jesus was more than just a teacher. He was a man who called himself “The Son of Man,” a term from the Book of Daniel for the figure who God ordains to judge and rule the earth (Daniel 7). He was a teacher whose most constant message was about the Kingdom of God, particularly that the kingdom had arrived: God’s long-promised reconciliation with his people had come. Jesus told his audience in many ways that he was the answer to their concerns about how to reconcile with God.

Fourth, calling Jesus a rabbi helps us understand why Jesus and his followers framed Christianity as Judaism fulfilled. Jesus regularly frames himself as the savior that his audience had waited centuries for, fulfilling all of God’s promises (although not in the way most people expected). The apostle Paul preached in synagogues first, Gentiles second, whenever he came to a new town because he saw Jesus’ message as the capstone to Judaism, not a totally new religion. The New Testament epistles consider many ways that Jesus fit Old Testament images (a prophet, a sacrificial lamb, a priest, a king). Christianity later became more associated with Gentiles, but the fact Jesus was called a rabbi reminds us his message is rooted in Jewish hopes. For centuries, God’s people wondered when God would make all things right, and Jesus came as the answer.

Photo Credit: ©Getty Images/chameleonseye

This article is part of our catalog of resources about Jesus Christ and His life, teachings, and salvation of mankind! Discover more of our most popular articles about the central figure of Christianity:

When was Jesus Born? Biblical & Historical Facts

What Language Did Jesus Speak?

Why Is Christ Referred to as Jesus of Nazareth?

How Old Was Jesus When He Died?

What Did Jesus Look Like?

What was the Transfiguration of Jesus?

Jesus Walks on Water - Meaning & Significance

Why Is it Important That Jesus Was Jewish?

.jpg)