Verse of the Day

You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives.

Verse of the Day

You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives.

Most Popular

-

7 Biblical Assurances Your Faith Is Real

Britt Mooney -

Morning Prayers to Start Your Day with God

Christianity.com Editorial Staff -

Is Masturbation a Sin?

Heather Riggleman -

What Is Passover? Bible Meaning and Connection to Christ

Christianity.com Editorial Staff -

7 Passages for Struggling Married Couples

Alicia Searl

Our Contributors

Joel Muddamalle Ph.D.

Author/Director of Theology at Proverbs 31 Ministries

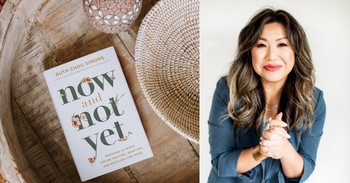

Ruth Chou Simons

Author

Dana Che Williams

Author/Coach/Podcast Host

.jpg)

Jamie Ivey

Author/Podcast Host

Alex MacFarland

Speaker

Around the Web