As the early light of dawn crept through the darkness, haze, and smoke, three men in a small boat tensely waited. They were torn between a fearful apprehension and hopeful expectancy. Daylight would show what lay ahead for their city and nation.

It had been almost twenty-five hours earlier when, finding themselves detained among the enemy ships, they watched the enemy launch a combined army-navy attack on one of their nation’s most important cities. Their country had already experienced many defeats, and their capital city had been burned. When the three men, then, found themselves observing the awesome attack launched against their fellow countrymen, their concern was great. The fighting was intense; the bombs from the enemy ships readily found their mark in the attacked fort. The noise of the rockets, bombs, and cannon-fire had been almost constant throughout the day and continued into the night.

An Eerie Quiet

Then in the early morning hours, there was silence. Only occasional firing broke the stillness. The battle seemed over, but what was the outcome? The three men in the boat watched eagerly to see if their flag was still flying over the fort and the city.

It was during those hours of intense watching and waiting that the words of a song began to take shape in the poetic mind of Francis Scott Key, one of the men in the boat. How did Key come to find himself watching the fate of his country from such a vantage point? What kind of a man was he to write a song that has ever since touched and thrilled his countrymen?

Pictured Below: A painting of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key was born on August 1, 1779, while the young United States was waging the war that would establish its independence. His father, John Ross Key, fought in the American Revolution and generously armed and equipped a regiment at his own expense. The Keys were wealthy landowners from Frederick, Maryland; and Francis Scott early developed a love for the land and home of Terra Rubra, his father’s estate.

Among the strong influences on Key’s character in his early years was his grandmother, Ann Arnold Ross Key. She had lost her eyesight by fire when she was rescuing two servants from the flames of her father’s burning house, but she bore her terrible affliction with Christian fortitude. The sensitive Francis Scott was deeply impressed by her strong faith. Francis stayed with his grandmother while he attended school in Annapolis. After graduating from St. John’s College at the age of seventeen, Francis went on to study law.

In 1802 Key married the beautiful Mary Taylor Lloyd in the elegant drawing room of the Lloyd mansion in Annapolis. The Keys had eleven children, six boys and five girls, and their family life together was a happy one. Soon after his marriage, Key began to practice law in Washington, D.C. Even in the busiest of times, Key never failed to conduct family prayers in his home twice a day, always including the servants in these family devotions.

The shady lawn and orchard of the Key mansion sloped to the edge of the Potomac River, providing a lovely setting for the frolics and gambols of the Key children. Francis Scott delighted in sharing the nature of the area with his children and often planned special surprises for them in the gardens. Once he instructed the gardener to make a tiny round garden for each child. When the seeds sprouted, they took the shape of the children’s names -- Marie, Lizzie, Anna, etc.

Key's Christian convictions were intense and influenced all his relations and actions. At one time, in 1814, he even considered entering the ministry. Though he decided to remain in his law career, his Christian beliefs continued strong and his Christian work active throughout his life. Among those whose faith Key’s help sustained was John Randolph of Roanoke. Randolph had had his faith shaken by reading Voltaire and other Enlightenment authors. In a letter to Randolph, Key wrote his own views, which still contain excellent apologetic advice for today:

I don't believe there are any new objections to be discovered to the truth of Christianity, though there may be some art in presenting old ones in a new dress. My faith has been greatly confirmed by the infidel writers I have read. Men may argue ingeniously against our faith, as indeed they may against anything -- but what can they say in defense of their own -- I would carry the war into their own territories, I would ask them what they believe -- if they said they believed anything, I think that they might be shown to be more full of difficulties and liable to infinitely greater objections than the system they oppose and they were credulous and unreasonable for believing it. If they said they did not believe anything, you could not, to be sure, have anything further to say to them. In that case they would be insane, or at best ill qualified to teach others what they ought to believe or disbelieve.

Into the Center of Conflict

When the United States went to war with Great Britain in 1812, Key was opposed to the war and thought his country’s action was precipitous; yet he joined the Georgetown Field Artillery Co. in 1813 and performed volunteer duty to defend his home. The times were tense, as the British successfully attacked and burned Washington, D.C., and moved towards Baltimore. Key had been sent to the British to negotiate the release of Dr. William Beanes, a civilian taken prisoner during the British march north from Washington. The British began their attack on Fort McHenry just as Key successfully finished his negotiations for the release of Dr. Beanes, but Key and his friends had to remain with the British throughout the battle. They intensely watched Fort McHenry's large flag to determine the outcome. As he watched and waited, Key wrote out the phrases to a song on the back of an envelope. Later the song was published as "The Defense of Fort McHenry" and enjoyed immense popularity when set to the English tune of "Anacreon in Heaven." Soon it was retitled "The Star-Spangled Banner." The title of the song became the name of the country’s flag, and because of the song, the country itself would ever after be known as the "Land of the free and the home of the brave."

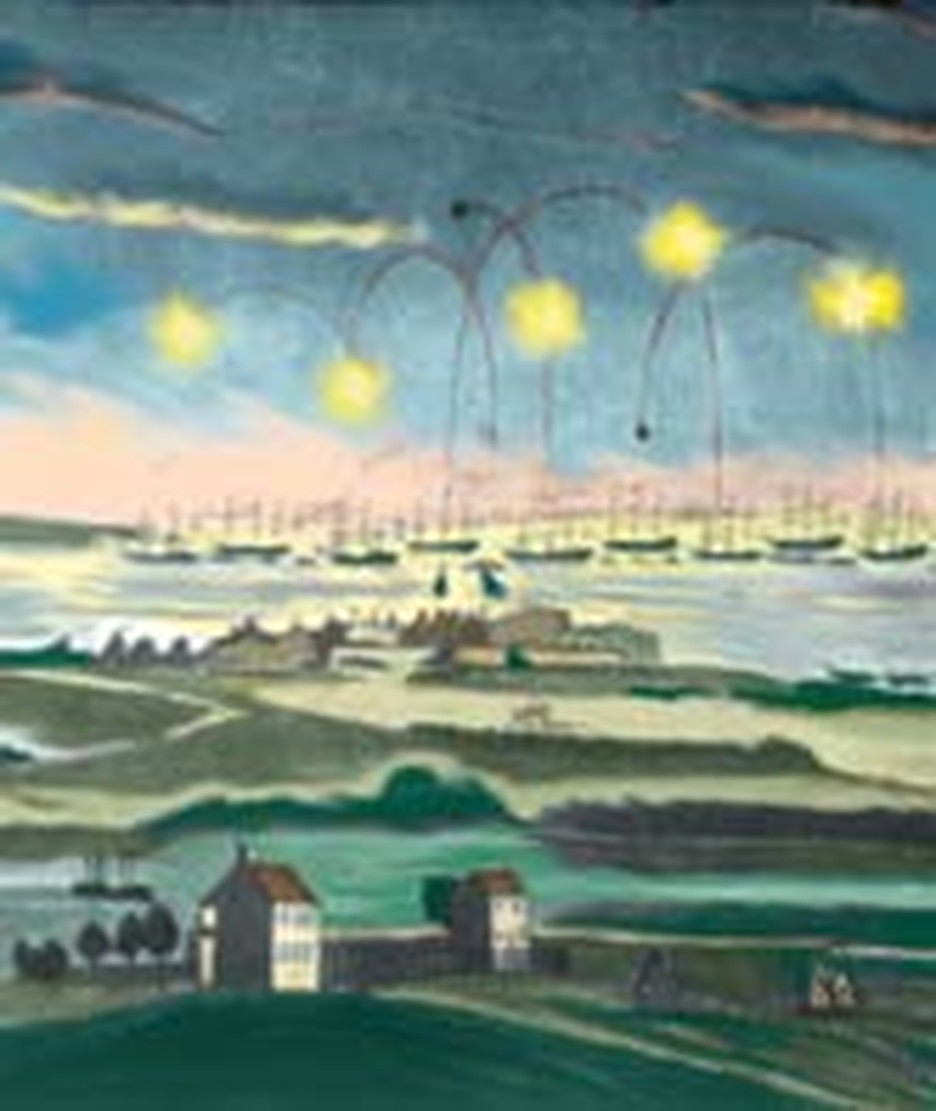

Pictured Below: "By Dawn's Early Light" a painting by Edward Moran depicting the moment of the morning of September 14, 1814. Francis Scott Key with his compatriots Colonel John Skinner and Dr. William Beanes spy the American flag waving above Baltimore's Fort Mc Henry.

Although written to rejoice in the victory of the moment, the last stanza describes what Key the Christian hoped would be a constant characteristic of his beloved country:

Oh, thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and war's desolation;

Blest with vict'ry and peace, may the Heav'n rescued land

Praise the Pow'r that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just;

And this be our motto: 'In God is our trust!

After the War of 1812 was over, Key continued his successful law career. For three terms he was district attorney for the District of Columbia. In both this position and as a private lawyer, Key argued many cases before the Supreme Court. President Andrew Jackson valued Key as a warm friend and entrusted him with several delicate missions. In 1832 he was sent to South Carolina by Jackson to help solve the nullification crisis, which was threatening dismemberment of the United States.

Though a member of the Episcopal Church with strong doctrinal beliefs, Key did not believe any particular form of church government was divinely established. He was tolerant in an age of much intolerance and willing to work readily with Christians of other denominations. Giving liberally to organizations he deemed worthy, Key was also instrumental in organizing several worthwhile causes. In Georgetown he helped organize the Lancaster Society for the free education of poor children. On a national level he was a founder and principal promoter of the American Colonization Society, one of the earliest societies devoted to dealing with slavery in America. Several theological institutions were either organized with Key's aid or administered by a board of which he was a member. These included the General Theological Society, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society, and the Virginia Theological Seminary at Alexandria. Even on his deathbed Key was concerned about helping others. He told his wife of the leather bag containing money for charity he had in his desk and instructed her how to use these funds for charitable purposes.

Death is not the End

Francis Scott Key died of pleurisy in the home of his daughter in January, 1843. Key’s earlier verses undoubtedly comforted his family as they laid him in the grave,

I have been a base and groveling thing

And now the dust of the earth my home,

But now I know that the end of my woe,

And the day of my bliss is come.

Then let them, like me, make ready their shrouds,

Nor shrink from the mortal strife,

And like me they shall sing, as to heaven they spring,

Death is not the end of life.