Why Do We Remember John Bunyan Today?

Share

Obstinate Preacher

To go free, all John Bunyan had to do was make one promise. He must agree not to preach publicly anymore. Bunyan's reply: "If I was out of prison today, I would preach the gospel again tomorrow by the help of God."

Older folk must have shaken their heads in wonder. "John Bunyan of all people! Why we remember when he was a filthy-mouthed ringleader in every sort of mischief."

John Bunyan's Beginning

Bunyan was born in 1628 in the heart of England, a mile south of Bedford a few years before the English Civil War. His family was so poor that when his father died, John was left only one shilling and his tinker's anvil. The boy had little formal education. However, he learned to read and feasted on medieval romances in which valiant knights underwent great trials and conquered villains and monsters. In youth he boasted a mouth so profane it shocked even wicked men. Additionally, he loved to dance, bell-ring and lead Sunday sports, all considered improper by Puritans. Although he attended church, he had little religious feeling.

Spared for Something

John turned sixteen in 1644 at the height of the Civil War. He joined the army. Since Bedford was a Parliamentarian stronghold, it is probable he served Cromwell. While on duty he was "drawn out" to take part in a siege. Another soldier asked to take his place. "[A]s he stood sentinel he was shot in the head with a musket bullet and died." John came to see this as proof God had spared his life for a great work.

Where Do You Want to Go?

Returning home, John married. He was twenty. His wife was as poor as he; between them, they did not have a dish or spoon. Her godly father had furnished her with two Christian books--books which John read with an increasingly troubled conscience. One Sunday as he played, he heard a voice. "Will you leave your sins and go to Heaven, or have your sins and go to Hell?" His distress was acute. He felt that he had sinned so gravely he was beyond forgiveness. Nonetheless, he struggled to find peace with God by obeying scriptural commands. Outwardly, he reformed and put off swearing and improper sports. Inwardly, he still longed to participate. He read the Bible. Although without peace, he thought God must be pleased with him.

One day he overheard four women speaking of their inner religious experience, and he realized he lacked something. Leaving the Church of England, he joined their fellowship. Still, he lacked peace. Only after reading Luther's commentary on Galatians did he realize he could be justified by faith alone. His inner struggles were not over, but he found relief. Bunyan felt compelled to tell others of faith in Christ. He became a field preacher. So effective were his words, people would arrive at dawn to hear him preach at noon.

When Preaching Was a Crime

Open-air preaching was illegal. Officials feared that demagogues would incite revolution. For this reason, John was careful never to side with any political faction in his teachings. All the same, he was in danger. Warned that he was to be arrested if he held church at a friend's house, he went anyway, determined to set an example of boldness. If he fled, weaker brethren would see it and run also. He was seized.

Without a hearing or witnesses, the judge sentenced John to three months in prison. Bedford's prison conditions were not the worst in England. Yet they were a genuine hardship. There was little light and no bathing facilities. The place stank of unwashed bodies. "Prison fever," or Typhus, killed many prisoners. The cells were overcrowded. John's ration was one-quarter loaf of bread a day. Worst of all, he was separated from his family. His first wife had died and he had remarried. He was not home to care for his children, including his blind daughter, Mary, whom he dearly loved. To support them, Bunyan made thousands of long, tagged shoelaces which he sold. Church members helped the Bunyans, too.

At the end of three months, John was offered freedom on condition he would no longer preach. Again he refused. The months turned to years. All in all, he spent twelve years in prison. Fortunately, a sympathetic jailer let John secretly slip off to meetings. He knew John would always return. Once he even let John go to London, but when his job was threatened, he forbade him to so much as peek out the jail door anymore.

Pictured Below: Bunyan in Bedford Jail

Life Behind Bars

For political reasons, Charles II released a number of prisoners. Bunyan was not among them. He was told he would have to apply for a pardon. He refused. To do so would be to admit he had done wrong. Elizabeth, his wife, pleaded for his release, but sympathetic court officers said John could go free only if he complied with the authorities. So John remained in prison. He was cheerful, believing he suffered for Christ. He had true freedom, he said. In prison, he could read the Bible, preach and sing hymns with no one to stop him. He was also allowed to write. While imprisoned he completed many of his sixty books, including the best known: Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners and The Pilgrim's Progress.

Pictured Below: The Wife Of John Bunyan Interceding For His Release From Prison

Bunyan's first book, Some Gospel Truths Opened According to the Scriptures, had attacked Quaker beliefs. Ironically it was Quakers who freed him. Told by the king to prepare a list of names for pardon, they included Bunyan's with their own members; names.

Released, Bunyan immediately returned to preaching. By now the authorities realized he was concerned only with the Kingdom of God. They jailed him again for six months in 1675, but otherwise, he remained free until he died at sixty years of age, having written The Pilgrim's Progress, the world's most widely circulated book next to the Bible.

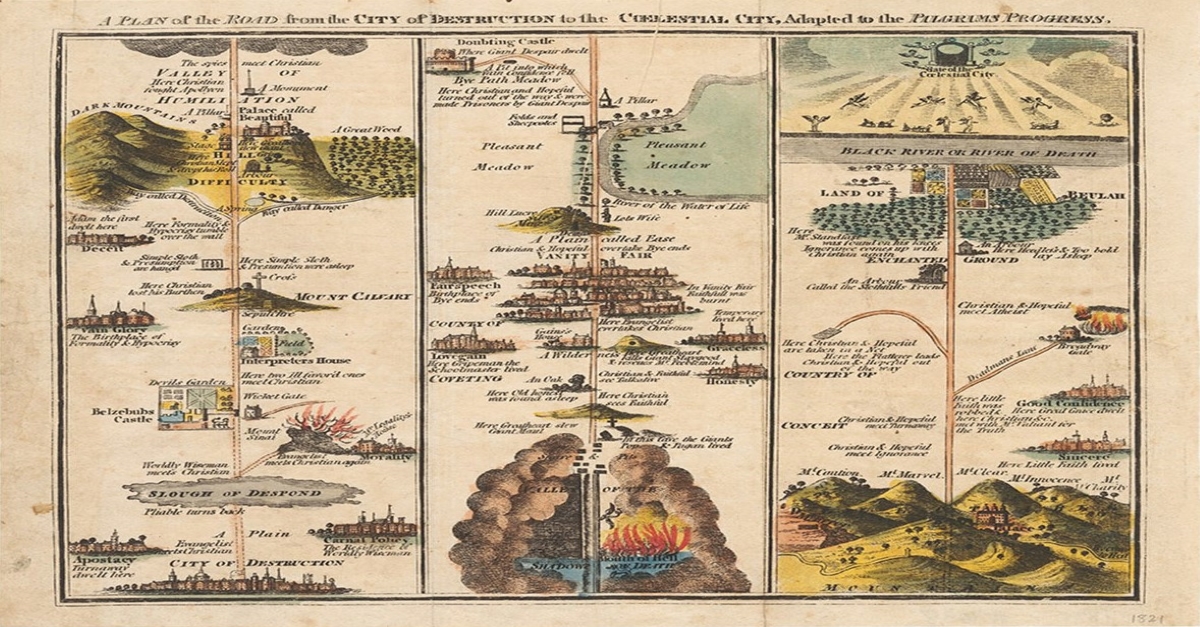

One of the unforgettable images from The Pilgrim's Progress is the heavy load that Pilgrim always carried around on his back. This crushing load was his sin which rolled away when he came to the cross.

Picture from Dangerous Journey:

Fascinating Facts. . .

- Bunyan's illegal imprisonment may have spared him from a worse fate. If he had been released and resentenced, he could have been banished from England under threat of hanging if he returned.

- Bunyan's fame was such that people came from all the midland counties to hear him speak. When told not to preach, Bunyan quoted I Peter 4:10, "As every man hath received the gift, even so, minister the same one to another, as good stewards of the manifold grace of God." His gift, he contended, was preaching.

- Many others besides Bunyan were held prisoner during this time, including Quaker founder George Foxe. Many of Bunyan's own church members were incarcerated with him during his twelve-year stay.

- When John was first sentenced to prison, his wife Elizabeth miscarried a child, adding to both their woes.

- Pilgrim's Progress as we know it isn't as Bunyan first wrote it. He issued several revised editions, adding new characters.

- Bunyan read and reread Foxe's Book of Martyrs while in prison.

My Own Self to Gratify

At the beginning of The Pilgrim's Progress, Bunyan gives an "author's apology," explaining how he came to write his now immortal work. Amazingly, he says he didn't write it with an expectation of publication, but for his own enjoyment.

When at the first I took my pen in hand Thus for to write, I did not understand That I at all should make a little book In such a mode; nay, I had undertook To make another; which, when almost done, Before I was aware, I this begun.

And thus it was: I, writing of the way

And race of saints, in this our gospel day,

Fell suddenly into allegory

About their journey, and the way to glory,

In more than twenty things which I set down.

This done, I twenty more had in my crown;

And they again began to multiply,

Like sparks that from the coals of fire do fly.

Nay, then, thought I, if that you breed so fast,

I'll put you by yourselves, lest you at last

Should prove ad infinitum, and eat out

The book that I already am about.

Well, so I did; but yet I did not think

To show to all the world my pen and ink

In such a mode; I only thought

to make I knew not what;

nor did I undertake Thereby to please my neighbor: no, not I;

I did it my own self to gratify.

Neither did I but vacant seasons spend

in this my scribble; nor did I intend

But to divert myself in doing this

from worser thoughts which make me do amiss.

From The Pilgrim's Progress, p.1

Indelible memories (Editor's Notebook)

The church I attended as a youth had Sunday evening church services. Do you remember them? I have to admit that the only messages from those services that I can vividly remember from before the age of about twelve were a series the pastor gave retelling the story of Bunyan's The Pilgrims Progress. The verbal images and names of people and places from Bunyan's allegory just never left me.

Then in seminary, I served as an assistant to Dr. William Nigel Kerr, a long-time lover of Bunyan, who over many years has gathered one of the largest collections of Bunyan editions and memorabilia. You could not be around Dr. Kerr for long without catching his enthusiasm for the Bedford tinker.

Bunyan captures us with vibrant imagery and creative genius that has crossed cultures, languages and centuries. But I think even more impressive is how Bunyan prompts us to appreciate the gifts and glory of God. It took an uneducated commoner to write this kind of common work that can arrest the attention of children (and adults) century after century.

- Ken Curtis

("John Bunyan" by Ken Curtis published on Christianity.com on April 28, 2010)

Further Reading:

The Life and Work of John Bunyan

Cover Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Thomas Sadler/Public Domain