What Kind of King's Kid Was She?

To look at her, you would not have guessed that Elizabeth was the daughter of a king and wife of a prince. In place of the gold-cloth dresses of her youth, she wore the plain gray robe of a Franciscan. Rather than be waited on, she washed lepers with her own hands. Instead of rich meats and pastries, she ate bread with a little honey, or a dry crust with a small glass of wine. She worked wool like any peasant girl. A Magyar knight, who saw her sitting by her little cottage, exclaimed in astonishment, "Whoever has seen a king's daughter spinning before?"

Well might he be astonished. Elizabeth von Thuringia was born in 1207 in the royal castle of Pozsony (Bratislava, Czechoslovakia). Her mother, Gertrude, was a committed Christian from a long line of Christians, and she imparted the faith to her daughter. Elizabeth's father, Andrew II, fought valiantly in the crusades but was not an exemplary king. His nobles forced him to sign Hungary's Magna Carta, the so-called Golden Bull. Two aunts and an uncle set examples of faith for their niece. Aunt Hedwig founded a convent for lepers, Aunt Mechthild became abbess of Kitzingen, and Uncle Egbert was bishop of Bamberg.

When she was not yet two, Elizabeth was pledged in marriage to the son of a Hungarian nobleman in Thuringia, then part of the German Empire. When she was four years of age, Elizabeth was sent to live with her prospective in-laws to be raised according to their customs at the Wartburg Castle.

Her Mother Killed

Gertrude was murdered in a political assassination when Elizabeth was seven. The grieving daughter was old enough to understand that she had a comforter in God, and she knelt with her troubles in the Wartburg chapel, praying for the souls of the murderers, although she experienced a terrifying dream in which she saw her mother's gory body. Shortly after, Elizabeth's fiancee also died. So her status in Thuringia became cloudy. However, Ludwig, the brother of her deceased fiancee, said he would like to marry her.

Her Dream Day

So when Elizabeth was just fourteen, her dream day came. In spite of attempts by Ludwig's family to send the beautiful olive-complexioned girl away, declaring her too holy to make a suitable bride, she was married to him as planned in a ceremony held in St. George's Church in Eisenach. Elizabeth listened well as the bishop read the ceremony and understood that, although she was entering a union with her husband, she could in some sense also experience a mystical union with Christ. In time she would. Meanwhile, Ludwig and she bound themselves to rule justly and to open their home in hospitality to monks and nuns. Ludwig was a young man of noble mind who took as his motto "Piety, Chastity, Justice." Elizabeth adored him.

Elizabeth brought great wealth to the marriage and now possessed more. She had the choice of five castles to live in and so she was called "Elizabeth of many castles." But wealth did not impress her. Although she dressed handsomely, in brocade dresses with round necks and sleeves that flared from her elbows, or bright flowing Hungarian silks that hugged her womanly figure, she said she did so only to please her husband. They lived at first on the Danube, and Elizabeth rode across the shattered nation with Ludwig, viewing firsthand the devastation left by the Golden Bull revolt of the Hungarian nobles. But when she became pregnant, she moved to Kreutsberg castle.

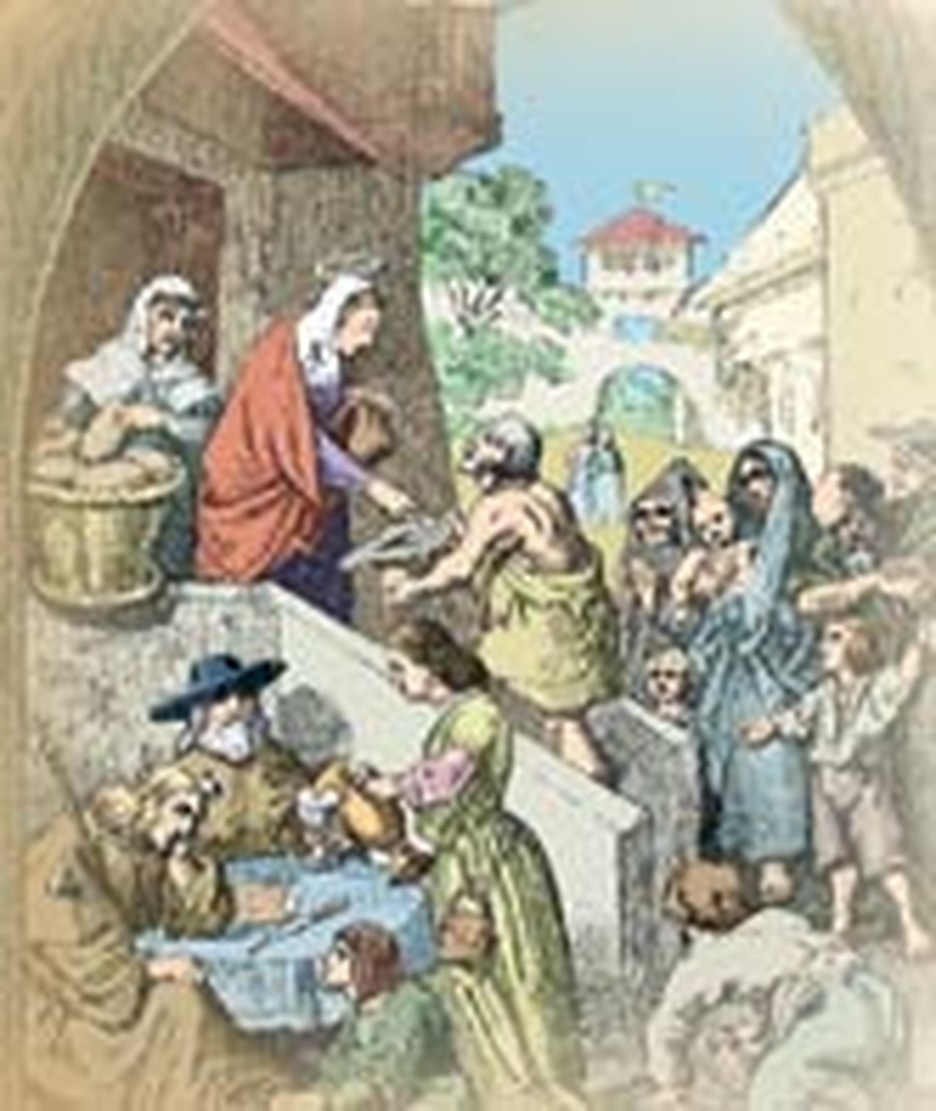

At the birth of her son, Herman, she carried him in her arms and walked barefoot to St. Katherine's chapel where she recited Psalm 127: "Children are a heritage of the Lord, and the fruit of the womb is his reward." She did the same for two other children, consecrating them to the Lord. Affected by Franciscans St. Francis of Assisi was preaching in those days, calling people to repent, cast aside the chains of wealth, and show kindness to the poor and lepers. Franciscans arrived in Thuringia in 1221 and their message stirred Elizabeth. It corresponded to the goodness she had learned from her parents. She longed to share her own blessings with the poor. Placing herself under the instruction of Brother Rodeger, she opened eastern Europe's first orphanage and tended lepers, undertaking even the dirtiest jobs of their care with her own hands. This outraged her in-laws.

Who's Been Sleeping in My Bed?

According to legend, she even laid a leper in her husband's bed. "Come my son," said her mother-in-law to Ludwig. "You shall see one of the wonders your Elizabeth works that I cannot prevent . . . ." When she flung back the covers, Ludwig did not see the leper, but rather Jesus lying on the bed. Whatever the reality behind the legend, Elizabeth's husband gave her funds to establish a leprosarium below Wartburg castle, so that weak lepers would not have to struggle up the castle path, which was so steep it was called "the knee-smasher." She poured relief upon all who were in true distress, giving the able-bodied tools to work with and the dying beds to lie on. Ludwig defended her good works against his family's criticism, saying that such deeds would bring blessing upon the country.

Was Her Generosity Excessive?

In 1226, severe famine raged in Thuringia, and on its heels brought crime and disease. Ludwig was away. Elizabeth feared that the people might revolt, for they were so desperate for food they ground up pine bark as a substitute for flour. When they crowded against the castle gate, crying for food, she ordered her reserves emptied for them and ran the ovens day and night, baking bread. With the help of monks and nuns, she set up soup kitchens across the country. Churches were thrown open to house the homeless, and she had firewood distributed to the weak. To the fury of her grasping in-laws, she took all the ready money in the treasury and distributed it among the sick. She even sold most of her jewels and a silver cradle she had been rocked in.

Who Did it Belong to Anyway?

Ludwig's stewards and treasurers met him on his return, accusing Elizabeth of bankrupting the treasury. Ludwig asked if she had lost any of his domains. The stewards had to admit she had not. Elizabeth saw only that she had saved precious lives and possibly Ludwig's kingdom itself. "I gave God what was his and God has kept for us what was yours and mine," she told her husband. He appreciated her more than ever. To fulfill a vow he had made, Ludwig joined Frederick II's crusade, leaving his lands in charge of his brother, Henry Raspe IV. Elizabeth had a premonition that Ludwig would not return, and dressed herself in widow's black. She was pregnant. After her child's birth, she learned that her husband had indeed died of fever. "The world is dead to me and all that was pleasant in the world," she cried and ran through the castle, shrieking like one crazed.

Thrown Out Without a Penny

At this point accounts differ. Some say her brother-in-law seized power, throwing her out of the castle, others that she left on her own accord. Claiming that she had ruined the treasury with her excessive concern for the poor, Henry cut off her allowance. In some accounts it is said that for spite, he forbade anyone in Eisenach, her nearby wedding town, to assist her. Alone, separated from her children, she walked to Eisenach on a mid-winter evening. Despite her misery, she joined the Franciscans in singing unto the Lord. Because they feared Henry's reprisals, none of the townsfolk would open their doors to her. Even the convent turned her away. She was forced to spend the night in the courtyard of an inn among jars and baskets. She prayed that Christ would forgive those who had wronged her.

The next day some faithful ladies brought her children to her. She hugged the little ones and said to Herman, "May God so love me, I know not whither to turn, or where to rest your little bodies, though all the lordship of this town is yours, dear son." Her loyal ladies promised to follow her wherever she went. They took refuge in the church that night. A poor priest brought them into his own home, and Elizabeth sold the few small jewels she was wearing so that they could buy food. A few days later, a wealthy townsman gave them a corner in his house.

As she prayed, Elizabeth reflected on Christ's sufferings. Her Lord, too, had been outcast, and borne cruel abuse. She asked Him to be with her, saying she desired never to be parted from Him. The Lord showed Himself to her in a vision and said, "If you desire to be with me, I desire to be with you." We know nothing certain about her vision except that she refused to wear crown jewels when entering church to meditate on Christ, because she had seen Christ crowned with thorns, and thought it unfitting for her to enter His presence crowned in gems.

Reinstatement

The crusaders who had ridden forth with Ludwig spoke up for Elizabeth. They demanded that her full domain be restored to her. For her part, she asked only for the restoration of her son's rights and her dowry so that she might have enough money to carry out good deeds. Eventually she gained her point and her inheritance was restored. Elizabeth tried living in a castle which was hers by dowry and later another which was hers by right of marriage, but Henry's ill-will was so great that she finally built a simple cottage and hospice in Wehrda, near Marburg. Later Elizabeth became a lay Franciscan --the first in the German Empire.

She devoted the revenues from her dowry to building a hospital where she attended the sick and spun wool. For extra income, she fished. Hers was one of Europe's first leprosariums. Many more followed and helped wipe out the disease from Europe. Dead of Exhaustion at 23 years old However, she overdid her exertions and died, probably of exhaustion. As she lay dying, she was heard singing in response to a bird upon the wall. At cock-crow of her last day, she said, "It is now the time when [Christ] rose from the grave and broke the doors of hell, and He will release me." Her body was laid in the little chapel she had attached to her hospice.

The blind, the lame, the demon possessed and lepers came to her funeral. A mere four years later, the Church named her a saint. Two hundred thousand people gathered for the occasion, convinced that Elizabeth had entered into a castle far grander than any of the five she had inhabited while alive on earth. For centuries, her self-sacrifice inspired works of literature and art.